Nobody knows exactly what Jesus looked like. So why is He commonly depicted as a pale, long-haired man? What is the origin of the common picture of Jesus?

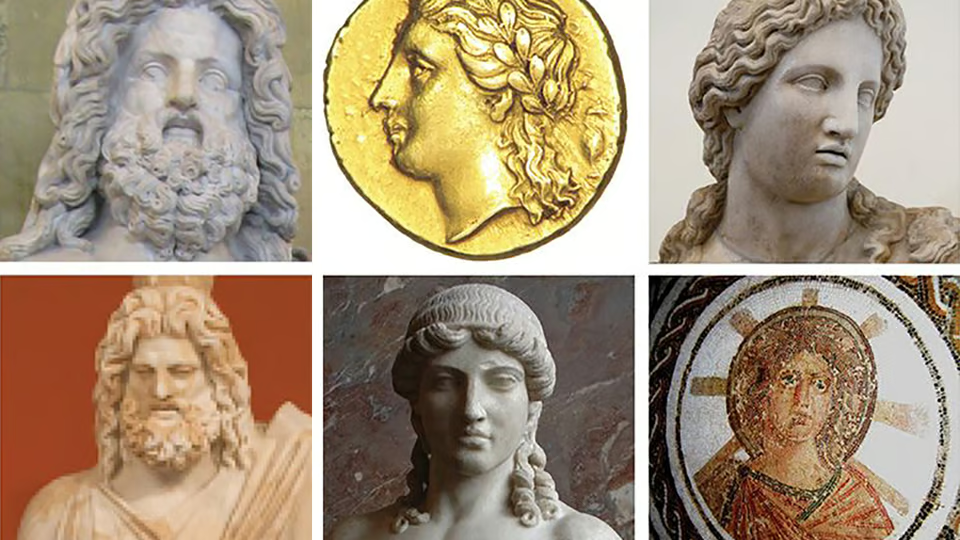

Images of Jupiter, Neptune, Serapis and Apollo influenced the religious art supposedly depicting Jesus.

It is the face known around the world. Though it sometimes appears with different shades of skin, the general characteristics are consistent: long hair, a beard, and a slender and somber face. This face is portrayed through paintings, sculptures, crucifixes and movies.

It is the face immediately recognized as Jesus Christ.

But, as we show in our article “What Did and Didn’t Jesus Look Like?” the Bible reveals very little about what Jesus looked like. And what it does reveal contradicts the popular image you may have in your mind—an image that has been planted there by artists and filmmakers.

Common differences between the depiction of Jesus and what He would have actually looked like include:

- Instead of having long hair, Jesus would have had short hair.

- Instead of having pale skin, He would have had a tanned complexion.

- Instead of being thin and fragile, He would have been masculine and strong.

But if this common depiction was not derived from Scripture, where did the popular image of Jesus come from? Why do artists, sculptors and film producers consistently portray Jesus with these features?

What history shows may surprise you!

Did the early Christian Church have images of Jesus?

The people closest to Jesus left no artistic descriptions of His appearance. This wasn’t just an oversight because they were busy. The New Testament is very deliberate in recording the most vital details about Jesus’ life—but notably there are few about His appearance. Nowhere do we find an artistic image of Him drawn by one of His contemporaries.

Why are there no paintings or drawings of Jesus that date back to His era?

Simply put, the early Christians understood that while Jesus was ordinary in appearance (Isaiah 53:2), He wasn’t an ordinary man—He was God in the flesh (John 1:1, 14; 20:28). Since they faithfully obeyed the 10 Commandments, they applied the Second Commandment to Jesus. Jesus Christ was God and should not be represented through images.

To learn more about God’s prohibition against idols and icons, read our article “Second Commandment: You Shall Not Make a Carved Image.”

The apostle Paul expounded on this when he said, “We ought not to think that the Divine Nature is like gold or silver or stone, something shaped by art and man’s devising” (Acts 17:29). In other words, God is so great that reducing Him to an image is like putting Him in a box. Paul relegated attempts to portray God through images to “times of ignorance” (verse 30). Paul was trying to combat idolatry—a major element of the Greco-Roman world he lived in.

Historian Jesse Lyman Hurlbut wrote of the first century: “Idol worship was interwoven with life in every department. Images stood in every house to receive adoration; libations were poured out to the gods at every festival; with every civic or provincial ceremony the images were worshiped. In such forms the [early] Christians would take no part” (The Story of the Christian Church, 1970, p. 41).

Secular history records, “The early Church had always been strict in forbidding the adoration of images and therefore did not want Christ’s face to be memorable” (Claudine Chavannes-Mazel, “Popular Belief and the Image of the Beardless Christ,” Visual Resources, Vol. 19, No. 1, p. 29).

It is clear from scriptural and historical evidence that the early Church had no images of Christ. So how did images and icons make their way into mainstream Christianity?

How images of Jesus crept into Christianity

Many changes occurred to Christianity after the end of the New Testament era. After the death of the original apostles, a small group of faithful Christians continued, but much of Christianity gradually began to evolve into a religion that bore little resemblance to the Church described in the book of Acts. You can read more about the transformation in our article “Was Christianity Designed to Evolve?”

The earliest images that have been uncovered supposedly portraying Jesus have been dated to around A.D. 240-256. Obviously, these artists, who lived 200 years after Christ’s ascension to heaven, had never seen Him or known any of His contemporaries.

Instead of trying to directly portray Him, these early images represented Christ symbolically. The most common was Christ portrayed as the “Good Shepherd,” holding a lamb. In these images, He is portrayed as young, physically fit and beardless. Most of these images were found in catacombs in Rome—not in Judea or Asia Minor, where the majority of early Christians lived.

The problem historians have in positively identifying these images as Christ is that they parallel Greco-Roman pagan art that used a shepherd image as a symbol of philanthropy (André Grabar, Origins of Christian Iconography, pp. 218-219). We will see that borrowing from pagan art is a common theme of many of the familiar icons of Christianity.

It wasn’t until after Constantine (272-337) that detailed artistic representations of Jesus began to be found in churches. Historian Paul Johnson wrote that “after the conversion of Constantine all the barriers [to the use of images] were broken down” (A History of Christianity, pp. 102-103).

In other words, before this time there was resistance to artistic portrayals of Jesus—but after Constantine accepted Christianity and started remaking it in the Roman image, the Greco-Roman customs of worshipping deities through statues and images became syncretized into Christianity.

“Towards the end of the fourth century, the use of images in the churches became general. People began to prostrate themselves before them, and many of the more ignorant to worship them. The defenders of this practice said that they were merely showing their reverence for the precious symbols of an absent Lord and his saints” (George Fisher, History of the Christian Church, 1915, p. 117).

Though there continued to be resistance, the use of icons and images won out and became entrenched in the Christianity that emanated from Rome and Byzantium. But the artwork of this emerging form of Christianity did not come out of nowhere. These images emerged from previous pagan imagery and traditions.

Where did this face of Jesus image come from?

After A.D. 400, images of Jesus began to be found all over churches, catacombs and even on the vestments of priests. Since the artists had no knowledge of Jesus’ real appearance, they developed their own images of Jesus with features that continue to influence art to this day.

Artists took the most notable characteristics of divinity from the Greco-Roman world and combined them into an image of a roughly 30-year-old man—devising the image recognizable as Jesus today: the slender, pale, bearded, long-haired Jesus.

The early images of Jesus portrayed Him slightly differently from how He is usually depicted today. Instead of being slender with a beard, early art depicts Him as a youthful, physically fit, clean-shaven, though somewhat effeminate, long-haired man.

Choosing to depict Jesus with long hair was not a random decision on the part of these early artists. They choose to portray Christ this way because the male gods of the Greco-Roman pantheon almost always were depicted with long hair. “In Greek and Roman art loose, long hair was a mark of divinity … in letting his hair down Christ took on an aura of divinity that set him apart from the disciples and onlookers who are represented with him” (Thomas Mathews, The Clash of Gods, 1993, pp. 126-127).

Many historians recognize that the early images of Jesus were directly based on the common features given to the sun god Apollo. Notice these enlightening quotes:

“When Christ is given a youthful, beardless face and loose, long locks it assimilates him into the company of Apollo and Dionysus. … Insofar as he copied the look of Apollo or Dionysus, he assumed something of their feminine aspect as well” (ibid., pp. 126-128).

“The clean-shaven visage more resembles the representations of Apollo or the youthful Dionysus, Mithras, and such semi-divines or human heroes as Orpheus, Meleager, and even Hercules. A youthful appearance recalls the divine attributes most associated with personal savior gods” (Robin Jensen, Understanding Early Christian Art, 2000, p. 119).

“Jesus’ representation as a version of Apollo/Helios in the Vatican necropolis demonstrates the way the Roman gods were directly challenged; Jesus usurps their place, often with iconographic attributes that make him quite similar in appearance to various pagan deities” (ibid., p. 120).

Look at these images of Apollo and note the similarities to many of the early artistic portrayals of the youthful Jesus:

Later artists wanted to capture the wisdom and power of Jesus as the “heavenly judge.” These artists turned for inspiration to the more powerful and authoritative gods in the Roman pantheon, such as Jupiter (the Roman version of Zeus), Neptune and Serapis. These gods, like Apollo, wore long hair to distinguish them from mortals, but were also distinguished by beards (which symbolized their wisdom and authority).

These characteristics found their way into artistic portrayals of Jesus. Notice these quotes from historians:

“The representation of Christ as the Almighty Lord on his judgement throne owed something to pictures of Zeus” (Henry Chadwick, The Penguin History of the Early Church, 1967, p. 283).

“A full-bearded face suggests authority, majesty, and power and may be seen in the portraits of the senior male deities of the Roman pantheon—Jupiter and Neptune, or even the Egyptian import, Serapis. … The mature and bearded figure perhaps emphasizes Jesus’ sovereignty over the cosmos. Here Christ takes Jupiter’s place in the pagan pantheon, and the iconography makes that displacement explicit” (Jensen, pp. 119-120).

“It was only after Constantine, about the time of Damasus, that the picture of Jesus was changed from the youthful wonder-worker to the royal or majestic Lord. At that time, Jesus shifted more to a bearded, elderly, dominant figure” (Graydon F. Snyder, Ante Pacem: Archaeological Evidence of Church Life Before Constantine, p. 298).

Notice the images of Jupiter, Neptune and Serapis:

Artists took the most notable characteristics of divinity from the Greco-Roman world and combined them into an image of a roughly 30-year-old man—devising the image recognizable as Jesus today: the slender, pale, bearded, long-haired Jesus.

Warnings about idolatry in the Bible

A consistent biblical theme is God’s abhorrence of pagan idolatry. God strictly commanded His people not to make images of Him (or any made-up god) or to use those images in worship. God was angry with Israel because of their attempt to worship Him through an image of a golden calf (Exodus 32; 1 Corinthians 10:7). Ancient Israel went into captivity because they embraced idolatry (2 Kings 17:15-18; Hosea 8:4).

The New Testament is filled with admonitions to “flee from idolatry” (1 Corinthians 10:14) and to “keep yourselves from idols” (1 John 5:21). The apostle Paul made many enemies in Ephesus for preaching against images “made with hands” (Acts 19:26).

Would a God who inspired these statements want to be worshipped and imagined through images inspired by pagan idolatry? Would a God who allowed no images of Himself want to be worshipped through made-up images?

Did the God who declares Himself “the same yesterday, today, and forever” (Hebrews 13:8) suddenly change His mind about images in the fourth century?

Some will counter with the argument that the modern use of imagery in Christian worship is not idolatry, but is instead imagery to help the human mind focus on and imagine the true spiritual God behind that imagery. The problem with this argument is that it is the same belief that the majority of pagans have had down through history. Most pagans believed there were real spiritual deities behind those images.

The Greeks who worshipped images of Zeus didn’t believe statues of Zeus were literally Zeus—they believed Zeus was a literal deity who lived on Mount Olympus. The statue was merely an aid, or a representation of Zeus.

Develop a biblically accurate image of Jesus

When we try to portray God through a physical image, we lose sight of the full extent of His power and grandeur, which can never be captured in stone or on canvas. Instead of viewing Him with the lens He gives us in His Word, we view Him through the lens of the human imagination. In a sense, we remake Him in our image.

Not only do the depictions of Jesus mischaracterize what He looked like, but they are images based on false gods of ancient paganism.

The best way to replace these images with the truth about Jesus is to diligently study your Bible and fill your mind with the knowledge of His teachings—while avoiding man-made images of Him.

Jesus Christ made a powerful statement recorded in John 4:23-24: “But the hour is coming, and now is, when the true worshipers will worship the Father in spirit and truth; for the Father is seeking such to worship Him. God is Spirit, and those who worship Him must worship in spirit and truth.”

Worship of Jesus Christ should be fully based on truth, not false artistic renderings of His appearance.