To modern Bible readers, the “kinsman-redeemer” is a puzzling figure, but his role sheds light on the character of Christ. Just what is a kinsman-redeemer?

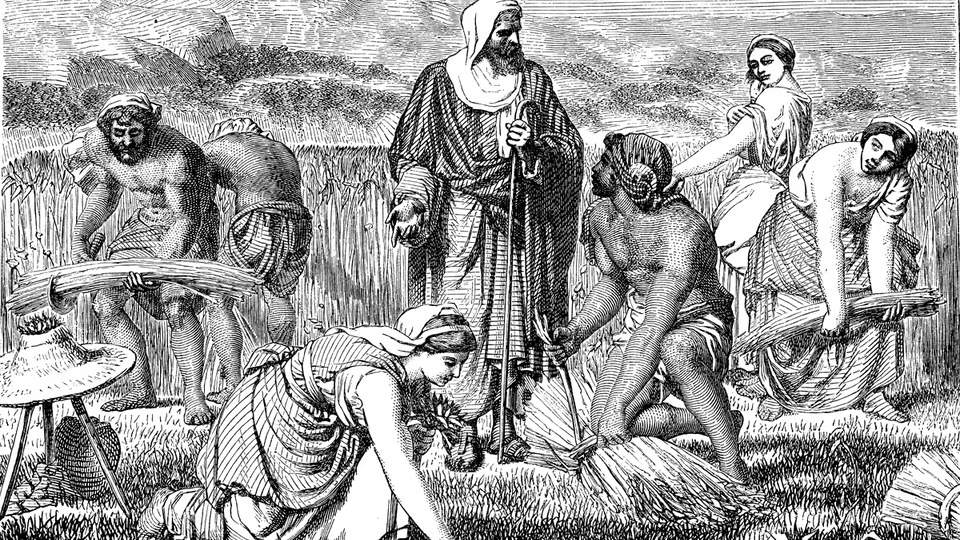

Illustration of Ruth and Boaz, who became her kinsman-redeemer.

Image Credit:ilbusca/DigitalVision Vectors via Getty Images

The wealthy farmer took his seat among several of the leading men of Bethlehem at the city gate, waiting for a relative to pass by. When Boaz, the farmer, saw his relative, he called out to him, asking him to sit down (Ruth 4:1).

Boaz was there to fulfill the duties of the kinsman-redeemer on behalf of a Moabite widow (Ruth 3:13). But what were those duties, and what is a kinsman-redeemer anyway?

Understanding the need for the kinsman-redeemer

Before we can understand the role of the kinsman-redeemer, we must first consider the social structure of Israel before the monarchy. Israel was not a nation in the modern sense of the word.

Aside from the priesthood and tabernacle, power and authority were dispersed among the tribes, each of which had its own leaders, who were supposed to judge righteously (Exodus 18:21).

Much of the security and social order that we take for granted in our modern nations was left to the tribes and even to the individual family groupings in Israel.

It was the extended family that served as the main safety net in tribal Israel. Families worked together, protecting one another and helping one another.

The role of the kinsman-redeemer

That’s where the kinsman-redeemer came in. This individual would always be a close relative who had the necessary resources to assist the poor and to seek justice on behalf of family members who had been wronged.

Like the kinsman-redeemer of the Old Testament, Christ, our Elder Brother, is a Kinsman, and He is both willing and able to fulfill the duties of the kinsman-redeemer on our behalf.

According to Vine’s Complete Expository Dictionary, “The kinsman-redeemer was responsible for preserving the integrity, life, property, and family name of his close relative or for executing justice upon his murderer” (“To Redeem”).

Vine’s and other biblical references use the term “kinsman-redeemer” to translate the Hebrew word gā'al (Strong’s H1350). However, you won’t find the term “kinsman-redeemer” in such popular translations of the Bible as the King James Version, the New King James Version, the English Standard Version, the New American Standard Bible, the New International Version, the Revised Standard Version or the American Standard Version.

Perhaps one reason this compound word is used in biblical reference material is that, when used as a noun, the Hebrew word is most commonly translated as either “kinsman” or “redeemer” in the King James Version. There is no single English word that conveys the full meaning of the Hebrew.

The Promised Land

To appreciate the significance of one of the major functions of the kinsman-redeemer, we must consider the importance of land in ancient Israel.

God had promised and given land to His people (Exodus 12:25; Deuteronomy 19:8). His purpose was not limited to providing a home to the 12 tribes, but to give every family unit what it needed to provide for itself.

The leaders received God’s direction in apportioning the land by casting lots (Numbers 33:54). Although families could choose to sell their properties, the land was to return to the original family unit every 50 years (Leviticus 25:10) on what was called the Jubilee.

God clearly stated that He owned the land, and that He was the One who had given them the land to work: “The land shall not be sold permanently, for the land is Mine; for you are strangers and sojourners with Me” (Leviticus 25:23).

In the tribal period, the kinsman-redeemer performed four important roles. The first was directly related to the land, and all these roles contributed to the stability and order of Israelite society.

1. The kinsman-redeemer and the land

God knew that some Israelites, whether due to their own poor choices or due to circumstances, would be forced to sell their land to pay off debts. But doing so would also mean losing their only real means for producing what they needed to survive.

His law, however, provided them with the possibility of regaining the land. This could occur through the help of a close relative with the resources and willingness to help (verse 25).

Although any relative could function as a kinsman-redeemer, the closest relation had the first opportunity to act. If the closest could not act, or would not, the next in line would then have the opportunity (Ruth 4:3-4).

Scripture makes it clear that families had a right to redeem the land at a fair price, calculated by counting the number of harvests between the year of sale and the next Jubilee (Leviticus 25:27).

2. The kinsman-redeemer and slaves

God prohibited the people of Israel from purchasing their fellow Israelites as slaves. Instead, He commanded that they be treated as hired servants (Leviticus 25:39-40), thereby enjoying greater freedom.

It was also possible for impoverished Israelites to sell themselves to sojourners, or foreigners dwelling in the land. The law provided for redemption from servitude, allowing family members to buy their poor relatives back (verses 47-49).

As with the land, the price of redemption was calculated based on the number of years remaining until the Jubilee (verse 50). Whoever performed this act of mercy and grace functioned as the kinsman-redeemer.

3. The kinsman-redeemer and offspring

In the ancient world, having children was very important, sometimes necessary just for survival. Unlike our modern society, there was no pension, retirement account or government social insurance in place. Israel’s civil laws did have provisions to help prevent and alleviate long-term poverty, but in general, poor elderly people relied on their adult children to take care of them.

The lack of offspring became a significant problem when the husband died, leaving his widow without any means of support. Once again, God provided a solution through what is called levirate marriage.

The dead man’s brother had the obligation to marry the childless widow, and the firstborn son would become the heir of her dead husband (Deuteronomy 25:5-6). The brother could refuse, but dishonor followed (verses 7-10).

This passage in Deuteronomy does not use the Hebrew word gā'al in reference to the brother’s duty. Even so, it is apparent that in the absence of a brother to raise up offspring, the kinsman-redeemer should step in.

We see this in the book of Ruth. In fact, the Jewish Encyclopedia asserts that Ruth’s situation “is not one of levirate marriage, being connected rather with the institution of the Go’el [a related Hebrew word]” (“Levirate Marriage”).

4. The kinsman-redeemer and justice

The kinsman-redeemer had a fourth, grim duty—to kill anyone who had murdered a family member (Numbers 35:19). This task, however, should not be compared to blood feuds or personal vendettas. It was a means of carrying out God’s will.

The biblical passages describing this duty have the same Hebrew word gā'al. However, for these verses, the word is generally translated as “avenger of blood” (NKJV, ESV, NIV) or something similar, such as “blood avenger” (NASB).

The law placed restrictions on the avenger of blood. God told Moses that the avenger of blood could not execute someone guilty of manslaughter “until he stands before the congregation in judgment” (verse 12). Neither could he execute the manslayer if he was in one of six cities of refuge or after the death of the high priest (verses 13, 26-28).

This is clearly different from a feud or vendetta. There would be a trial to determine whether the death was accidental or premeditated.

What this means is that the blood avenger sought justice on behalf of the family member who had been killed. He served as executioner for premeditated murderers, but his presence also kept an individual guilty of manslaughter confined to the city of refuge.

Ruth and her kinsman-redeemer

With this review of the duties of the kinsman-redeemer, we can understand more about what Boaz was doing when he called out to his relative to sit with him at the city gate. It was his intent to protect and provide for family members who had fallen on hard times.

Boaz performed two of the four roles of the kinsman-redeemer on behalf of Ruth and Naomi. He went to the city gate because in the ancient Near East, important business and legal transactions were conducted there in the sight of witnesses.

As Boaz spoke with his relative, he laid out the first duty, that of redeeming the land that had belonged to Naomi’s husband, Elimelech (Ruth 4:3). At first, the closest relative was willing to redeem the property, but he changed his mind when he learned that he would also need to provide an heir to take care of Ruth and Naomi (verses 4-6).

Stepping in as a kinsman-redeemer was considered a sacred duty, an obligation toward one’s family. Just as refusing to provide the widow of one’s brother with an heir brought dishonor (Deuteronomy 25:7-10), refusing to fulfill the role of kinsman-redeemer brought shame.

Even so, the closest relative refused. As Expositor’s notes, “It appears that he was [at first] willing because she had no heirs, and he thought the fields would revert to him. When he learned that he must also marry Ruth, the widow, and raise up an heir who would get the property, he refused and gave way to Boaz, the next kinsman in line” (Vol. 2, p. 636).

Boaz was willing to do both tasks for family members in need. He redeemed the land of Naomi’s dead husband, and he had a son with Ruth who would grow up to take care of the two women (verses 13-15).

The Lord God as our Kinsman-Redeemer

The kinsman-redeemer was a well-known part of the social structure of Israel. And it also became an ideal metaphor for God’s relationship to His people.

The Zondervan Pictorial Encyclopedia of the Bible points out, “The outstanding example of redemption in the [Old Testament] was the deliverance of the children of Israel from bondage, from the dominion of the alien power of Egypt” (p. 49).

In the same way that a caring man with the resources to help a relative in need could redeem that individual from slavery or buy back his land, God cared about Israel’s needs. The Rock that followed them—Christ (1 Corinthians 10:4)—was willing and able to deliver them from slavery in Egypt, and He gave them the Promised Land.

God used the Hebrew gā'al to describe what He does as the Redeemer of Israel in Exodus 6:6. In this passage, He told Moses to tell the people of Israel that “I will redeem you with a stretched out arm.” He intended to function as the Redeemer for all His people.

Other biblical passages identify God as a personal Redeemer. Jacob (Genesis 48:15-16) and Job (Job 19:25) both recognized God as their individual hope for personal redemption.

The Kinsman-Redeemer in the New Testament

The New Testament often draws on this same concept to describe the work of Jesus Christ. Like the kinsman-redeemer of the Old Testament, Christ, our Elder Brother, is a Kinsman, and He is both willing and able to fulfill the duties of the kinsman-redeemer on our behalf.

The kinsman-redeemer of ancient Israel bought back the land of family members. In the same way, Christ laid down His life to redeem the world itself—we stand to inherit a world “set free from its slavery” (Romans 8:21, NASB).

For the people of ancient Israel, it was the avenger of blood who sought justice on behalf of family members who had been slain. Our God will do the same for us. Paul encouraged the church at Rome to leave justice to our God, who said: “Vengeance is Mine, I will repay” (Romans 12:19, quoting Deuteronomy 32:35).

In ancient Israel, the kinsman-redeemer provided widows with heirs to take care of them. In the same way, Christ has reassured all of His disciples that among other blessings, He will provide “brothers and sisters and mothers and children” to each of us through the Church (Mark 10:30).

Finally, the kinsman-redeemer of Israel purchased the freedom of family members who had sold themselves into slavery. Jesus bought us back from the worst type of slavery. He redeemed us from slavery to sin.

That redemption came at a tremendous cost: “Not with the blood of goats and calves, but with His own blood He entered the Most Holy Place once for all, having obtained eternal redemption” (Hebrews 9:12).

It is because Christ made this sacrifice that we can be free. Free from the sins that bring us so much pain. Free from the confusion that engulfs this whole world. Free from the hopelessness that we see everywhere.

And just as “the women said to Naomi, ‘Blessed be the LORD, who has not left you this day without a close relative’” (Ruth 4:14), we can say, “Blessed be the LORD, who has not left us without a Redeemer!”

Read more about redemption in our article “What Does Redemption Mean in the Bible?”