China and Russia are creating a partnership that is poised to dominate Asia and challenge the West. Where might it lead?

As American and European leaders gathered on the coasts of the English Channel in June 2019 to commemorate the 75th anniversary of the World War II D-Day landings in Normandy, another significant gathering was taking place in Moscow. This meeting aimed to cement and celebrate a new, perhaps even more powerful alliance for the 21st century.

Russian President Vladimir Putin welcomed Chinese President Xi Jinping to the Kremlin to mark seven decades of diplomatic relations between Moscow and Beijing. They called their ties “firm as a rock,” boasting that China and Russia will jointly serve as a “reliable guarantee of peace and stability” for the world.

Will such a coalition of nations assure harmony? What does Bible prophecy show will be the culmination of the union of eastern titans?

Just weeks later, as American diplomats visited the region, the two Eurasian national leaders underscored their deepening relations by testing their Asian adversaries. Vividly demonstrating their joint military capability, four Chinese and Russian nuclear-capable aircraft, flying in formation, breached the airspace of South Korea and Japan, prompting both nations to scramble jets and stoking tensions in the region.

Shifting global power eastward

China and Russia now present more than just a counterweight to the U.S. and other Western countries. According to a February 2018 Carnegie Endowment for International Peace report, these nations “seek to accelerate what they see as the weakening of the United States.”

“With a common desire to shift the center of global power from the Euro-Atlantic space to the East,” the white paper continues, “they aim to rewrite at least some of the rules of global governance.”

Not surprisingly, in the United Nations Security Council, where both nations are permanent members, they act in concert. They vote identically 98 percent of the time, and Russia has supported every Chinese veto since 2007.

“Their cooperation,” according to Douglas Schoen and Melik Kaylan, authors of the book The Russia-China Axis, “almost without deviation, carries anti-American and anti-Western ramifications. … Indeed, Russia and China exacerbate virtually every threat or problem facing the United States today” (2014, pp. 3, 5).

Ties that bind

One of America’s leading 20th-century strategic thinkers, former national security adviser Zbigniew Brzezinski, sounded an alarm in his book The Grand Chessboard. In analyzing threats to American security, he warned that “the most dangerous scenario would be a grand coalition of China [and] Russia … united not by ideology but by complementary grievances” (1997, p. 55).

Grievances and wounded national pride are powerful national motivators, and Moscow and Beijing have a growing list of complaints against Washington and the West. Constraints imposed by the U.S.-led global order are driving these Asian giants closer together.

Simultaneously mired in economic conflicts with America, “Russia and China have decided to work together more closely in large part because both countries are more worried about the U.S.,” wrote foreign affairs scholar Walter Russell Mead (“Why Russia and China Are Joining Forces,” The Wall Street Journal, July 29, 2019).

Last year, President Trump’s administration announced it was moving away from the war on terror, choosing instead to focus on deterring “strategic competitors” China and Russia. Mr. Trump blacklisted certain technology companies and levied a series of trade tariffs on exports from China, which the Treasury Department accused of being a currency manipulator.

The U.S. has also expanded its military presence in the South China Sea to block Beijing’s efforts to lay broader claims to it. The face-off against Russia has included the termination of a nuclear disarmament treaty, maintenance of economic sanctions against Russia for its occupation of Ukrainian territory and accusations of meddling in U.S. elections.

Two strongmen form a bond

Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi reportedly said in April 2018 that relations with Russia were at “the best level in history.” In June 2018 Xi Jinping reportedly declared Vladimir Putin to be his “best, most intimate friend.”

The strong bond between them—they have met 30 times in the past six years—acts as both the driver and, when needed, the shock absorber in the relationship.

Surveys of public opinion in 2018 show that 69 percent of Russians hold a negative view of the United States, while the same percentage of Russians hold a positive view of China. When asked who their enemies are, two-thirds of Russians point to the United States, ranking it as Russia’s greatest adversary. Only 2 percent of Russians view China as their foe.

Not natural allies

These two geopolitical powerhouses have a complex and contentious history, marked by mutual suspicion, commercial rivalries and ideological discord, punctuated by periods of intense hostility along their disputed 2,600-mile border. Russia’s eastward expansion across Siberia and the Russian Far East in the 1800s led to unequal treaties forcing China to cede over 1.5 million square kilometers (580,000 square miles) of territory to imperial Russia.

They were allies for a brief period after the Communist Party takeover in Beijing in 1949, when Moscow sent aid and advisers to China.

But following the death of Soviet leader Joseph Stalin, the regimes began trading barbs and then gunfire. In 1969 the sharp split led to a series of border skirmishes that brought them to the brink of nuclear war. The tense standoff lasted for years.

Because of that Sino-Soviet split, the U.S. and its Western allies have been relatively unconcerned about the emergence of such a cohesive bloc in the East. But in the last decade, as their relationships with Western nations soured, both Moscow and Beijing faced a stark choice of alliance or isolation.

Trade benefiting both partners

Though China’s economy is six times larger than Russia’s, the pairing has a certain logic because of Russia’s vast natural resources and China’s industrial prowess.

Russia and China have pointedly presented themselves as, in the words of Washington Post analysis writer Adam Taylor, “champions of free trade and opponents of protectionism, and both believe their export-driven economies are under threat” from the West.

Though China’s economy is six times larger than Russia’s, the pairing has a certain logic because of Russia’s vast natural resources and China’s industrial prowess.

China is rising as a global power with financial liquidity and a vast population, yet lacks many vital natural resources. Russia is failing economically but has the necessary know-how in key fields such as diplomacy, defense and space, while its demographically barren regions are loaded with timber, water, minerals, gold, oil and natural gas needing a market.

In 2010 China became the world’s largest energy consumer, surpassing the United States. And Russia recently displaced Saudi Arabia as China’s largest source of imported oil. A decade ago natural gas pipelines in Russia were all directed west toward Europe, but with the Power of Siberia pipeline—part of a 30-year gas deal worth $400 billion—coming onstream this year, China will become the second-largest market for Russian gas, just behind Germany.

Bilateral trade has shot up from $69 billion in 2016 to $107 billion last year. A merging of China’s ambitious Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) with Russia’s Greater Eurasian Partnership plan, aimed at the republics of the former Soviet Union, promises to form an impressive alliance with implications for Asia and Europe.

A new military union?

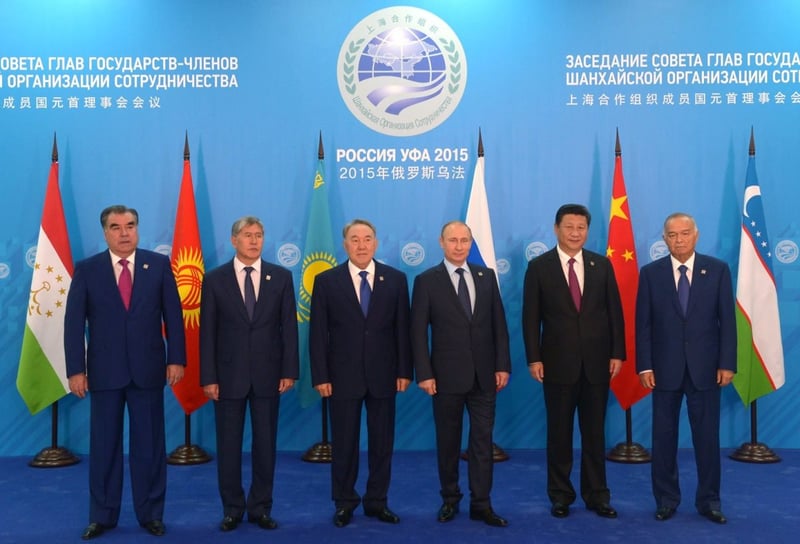

Shanghai Cooperation Organization

Vladimir Putin, recalling Soviet history with an eye for the future, has called SCO “a reborn version of the Warsaw Pact.”

This new Asian axis is emboldened by a perceived decline of American will to use military might to support allies around the world. Both Russia and China have been streamlining and modernizing their forces. Though the prospect of a full-blown military alliance remains remote at this time, joint naval drills and sales of advanced technologies and sophisticated weapon systems have become routine.

Highlighting this new partnership, last fall they participated together in Vostok 2018, the largest military exercise the world has seen since the end of the Cold War. This projection of military power involved hundreds of thousands of Russian troops that were joined by Chinese soldiers in what the South China Morning Post noted as “the ‘Shanghai spirit’ of mutual trust, mutual benefits and consultation” (Sept. 18, 2018).

New trade routes

Moscow and Beijing are also now jointly developing energy, transportation and telecommunications infrastructure in the Arctic. Believed to contain 13 percent of the world’s undiscovered oil and almost 30 percent of its undiscovered gas, the Arctic waters along Russia’s coastline are a potential shipping superhighway. The Northern Sea Route is designed to connect the Atlantic Ocean and the Pacific Ocean along the Russian coast of Siberia and the Far East as a vital part of China’s BRI infrastructure initiative.

China, which has begun to identify itself as a “near-Arctic state,” says the route is as much as 15 days faster than shipping from Western Europe to China through the Suez Canal.

Waiting for Europe

Europe, as a market and source of technology, remains key to China and Russia’s ambitions. With Europe continuing to be pulled apart by various internal frictions—Brexit, immigration and authoritarianism—it has not focused on the threat of a potential Eurasian juggernaut in the making.

A Eurasian super-alliance between Russia and China would, according to former European parliamentarian and author of Dawn of Eurasia Bruno Maçães, have a considerable impact:

“In the mind of the West, it would combine the fear associated with Russia with the apparent invulnerability of China. Washington would feel under attack; Europe, intimidated and unsettled. The old Continent would also face the threat of a split between Western Europe and the nations of Central and Eastern Europe, which could turn their focus east under the influence of a cash-happy China ready to invest in the region. It would be an entirely new world, and it’s one that is coming closer to becoming reality” (Politico).

The “world island”

The supercontinent of Eurasia is the largest landmass on earth, the home of 70 percent of the world’s population and two-thirds of its economic growth. Its sheer size, wealth and limitless potential has fascinated influential strategists for centuries.

Eurasia will be front and center in a series of titanic clashes at the end of this age.

More than century ago Halford Mackinder called Eurasia the “world island” and the center of geopolitics. His “heartland theory” proposed that whoever ruled the core of Eurasia would command the world.

Mackinder was, in a sense, quite correct, in that Eurasia will be front and center in a series of titanic clashes at the end of this age.

Eurasia in prophecy

While political leaders devise plans to dominate Eurasia, the God of the Bible boldly asserts that He alone can predict the future and bring it to pass (Isaiah 46:8-11). His prophetic words foretell the major role this region will play at the end of the age, so that we can know that He is in charge.

The prophetic book of Daniel addresses an end-time clash in which the king of the North—a revived European superpower with historical links to the ancient Roman Empire—will defeat the king of the South—a Middle Eastern conglomeration (Daniel 11:40-45).

The victorious and boastful European power is then disturbed by troubling news from the “east and the north” (verse 44). Using the modern nation of Israel as a reference point, to the north and east of Jerusalem are Russia and China. These Asian powers will move to oppose or counterbalance the European superpower.

Daniel’s prophecy continues with the European king preemptively launching an attack: “Therefore he shall go out with great fury to destroy and annihilate many” (verse 44).

The Eurasian colossus—known as the “kings from the east” in Revelation 16:12—will then counterattack the European power with an enormous army from east of the Euphrates River (Jeremiah 50 and 51) and will “kill a third of mankind” (Revelation 9:15). They will then move toward the Middle East for a final confrontation with the king of the North (Revelation 9:13-18 and 16:12) in what they expect will be a final battle for mankind.

These combined armies will be confronted and defeated by the returning Jesus Christ (Revelation 17:14; 11:15).

You can learn more about these events, as well as the good news of the incredible time period that will follow them, in our booklet The Book of Revelation: The Storm Before the Calm.