The Bible was primarily written in Hebrew and Greek. But a small portion, including several chapters in Daniel, was written in Aramaic. Why was Aramaic used?

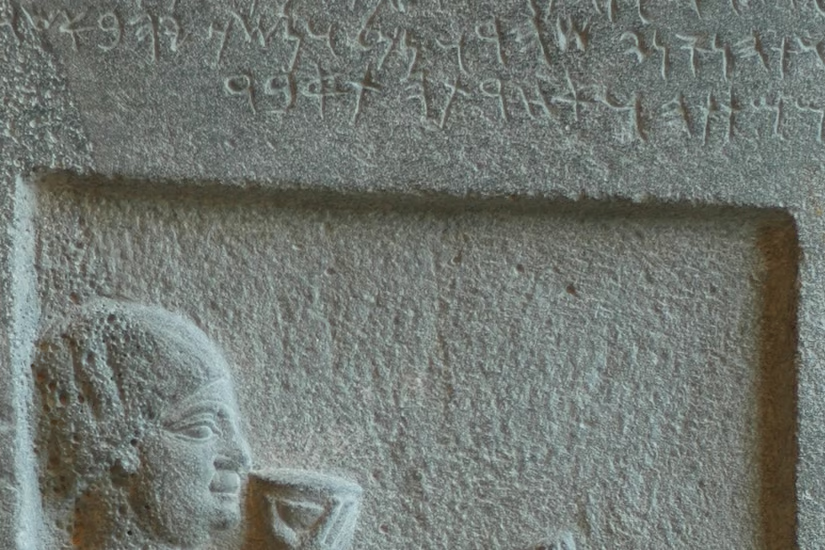

Aramaic inscription on a funeral stele from the seventh century B.C. in the Louvre (Wikimedia Commons photo).

Most students of the Bible know that the Old Testament was primarily written in Hebrew and that the New Testament was primarily written in Greek. But few realize that whole chapters of books in the Old Testament were written in Aramaic and that first-century Jews, including Jesus, spoke Aramaic. In fact, a few of Christ’s words, spoken by Him in Aramaic, are recorded in Aramaic in our English translations of the Bible.

The reasons for using Hebrew and Greek seem obvious. Hebrew was the language of the ancient Israelites, so it makes sense that this was the primary language of the Old Testament. Jews, who are also Israelites, continue to use this language today. Greek was the language of education during the first century. So it makes sense that the apostles used this language in their writings.

But why Aramaic? How did this language find its way into the Bible? What can we learn from the inclusion of Aramaic in the Word of God?

Aramaic and Abraham’s descendants

According to The International Standard Bible Encyclopedia, Aramaic is “a form of Semitic speech, most nearly related to Hebrew and Phoenician, but exhibiting marked peculiarities and subsisting in different dialects. Its original home may have been in Mesopotamia (Aram), but it … became the principal tongue throughout extensive regions. … In its eastern form it is known as Syriac. In its occurrence in the Old Testament, it formerly, though incorrectly, generally bore the name Chaldee” (“Aramaic Language”).

As a language closely related to Hebrew and spoken extensively in areas bordering Canaan, the descendants of Abraham had some exposure to Aramaic during the time preceding the establishment of the ancient nation of Israel. The first use of Aramaic in the Bible is found in Genesis 31:47 where Laban called the stone monument of peace between him and Jacob “Jegar Sahadutha,” Aramaic for “Heap of Witness.” Jacob called it “Galeed,” which means the same thing in Hebrew. In this case, the Hebrew name prevailed (verse 48).

Aramaic and the Jews

Hundreds of years later—after the descendants of Abraham had been slaves in Egypt and lived through the time of the judges and the Golden Age of Israel under Solomon, and the northern kingdom of Israel had been taken captive by Assyria—the great Assyrian army approached Jerusalem with the intent of subjugating the kingdom of Judah.

The Assyrian Rabshakeh, trying to intimidate the residents of the city, chose to speak in Hebrew—the language of the Jews. Isaiah 36:11 and 2 Kings 18:26 record Hezekiah’s officials asking the Assyrian leader to speak to them in Aramaic, so the people on the wall would not understand.

From this incident, it appears that “Aramaic was the ordinary language of Assyrian diplomacy” and that most of the Jewish populace did not speak Aramaic (ibid.). The ESV Study Bible adds that “Aramaic was the language of international protocol” (comment on Isaiah 36:11).

While God delivered the Jews from this Assyrian invasion, years later God allowed the nation of Judah to fall to the Babylonians (also called Chaldees). Shortly before the fall of Judah, the prophet Jeremiah admonished the Jews to resist idolatry in Jeremiah 10. Of particular interest is Jeremiah 10:11, which is written in Aramaic. This verse provides an answer for the Jews to give to people who might try to induce them to worship an idol: “Thus you shall say to them: ‘The gods that have not made the heavens and the earth shall perish from the earth and from under these heavens.’”

Albert Barnes’ Notes on the Bible states that this verse “was probably a proverbial saying.” It appears that God was giving the Jews a response to use when they would receive invitations to worship an idol by people who spoke Aramaic. And the Bible records that this did indeed happen.

Secular records indicate that there were at least three deportations of Jews from Judah to Babylon, where Aramaic was the language of the empire (Daniel 2:4). Shadrach, Meshach and Abed-Nego faced this very test regarding idolatry after having been deported to Babylon. The test was whether they would bow down to King Nebuchadnezzar’s idol (Daniel 3). As the king spoke to them, commanding them to bow down to his idol, perhaps the Aramaic answer in Jeremiah 10:11 came to their minds. For a more thorough examination of this incident, see “Daniel’s Three Friends.”

With so many Jews in captivity in the Aramaic-speaking empire, a great many Jews were now bilingual, speaking both Hebrew and Aramaic. “After the return from the Captivity, it [Aramaic] displaced Hebrew as the spoken language of the Jews in Palestine” (ISBE). This explains why the Jewish leaders who canonized the Old Testament were comfortable having both Hebrew and Aramaic in the sacred writings.

The longest passages in Aramaic in the Bible

We have already seen the places in the Old Testament where Aramaic was used prior to the Babylonian captivity of the Jews. We now come to the longest inclusion of Aramaic in the Bible, which is located in the book of Daniel, where chapter 2:4 through chapter 7:28 is written in the language of the Babylonians.

It is interesting to learn about the small portions of Aramaic that were included in the original writing of the Bible. But our study of God’s Word and how we need to live in accordance with God’s expectations is of even greater importance.

While people may wonder why God allowed such a large section of Scripture to be written in Aramaic, there is an important benefit from this occurrence that assists scholars today in determining the date of the writing of the book of Daniel. As noted in companion articles in this section of the website, some scholars have suggested that the book of Daniel was not written until the 160s B.C., which would have been after many of the very detailed events prophesied in Daniel 11 had already transpired.

But such reasoning for a late date for the writing of Daniel is proven to be in error by a careful study of the Aramaic text in the book. Addressing the style of Aramaic in the book of Daniel, The Expositor’s Bible Commentary notes: “But with the publication and linguistic analysis of the Apocryphon (which is a sort of midrash for Genesis) [written in the third century B.C.], it has become apparent that Daniel is composed in a type of centuries-earlier Aramaic” (“Introduction to Daniel”).

Incidentally, we should note that a study of the Hebrew used in the book of Daniel yields a similar result. As The Expositor’s Bible Commentary adds: “From the standpoint of linguistic science, there is no possibility that the [Hebrew] text of Daniel could have been composed as late as the Maccabean uprising.”

The next longest and final Old Testament passages written in Aramaic are found in the book of Ezra. The first passage in Aramaic (Ezra 4:8 through Ezra 6:18) begins with a letter of accusation that the Jews’ enemies sent to King Artaxerxes about the Jews rebuilding Jerusalem. The section continues with the king’s response, how the Jews reacted to the response and, finally, King Darius’ decree to allow the Jews to proceed.

The second section of Ezra in Aramaic (Ezra 7:12-26) is an official letter from King Artaxerxes allowing Ezra, and other Israelites who wished to do so, to take silver and gold to Jerusalem for the temple.

Aramaic in the New Testament

In the first century, Aramaic continued to be the language spoken at home by Jews. Because of this, a minority of scholars believe that parts of the New Testament may have first been written in Aramaic and then translated into Greek.

While the predominant view of scholars is that the New Testament was primarily written in Greek, the influence of Aramaic in the first century remains evident even in English translations of the Bible. Here are a few transliterated Aramaic phrases in the New Testament:

- The word Abba is found in Mark 14:36. Abba means “father.” Thus, Abba, Father actually means “Father, Father.” Although it might seem redundant, the former word is Aramaic and the latter is Greek. This phrase emphasizes the personal relationship that Christ had with God the Father and that we, too, can have with Him (Romans 8:15; Galatians 4:6).

- The Aramaic phrase Talitha, cumi in Mark 5:41 is followed by the phrase “which is translated, ‘Little girl, I say to you, arise.’”

- While healing a man who was deaf and who had a speech impediment, Jesus “said to him ‘Ephphatha,’ that is, ‘Be opened’” (Mark 7:34). The word Ephphatha is Aramaic.

- Regarding 1 Corinthians 16:22, The ESV Study Bible explains, “The phrase Our Lord, come! (marana tha) is Aramaic rather than Greek, probably representing an early Jewish Christian prayer for the return of Jesus.” The King James Version reads: “If any man love not the Lord Jesus Christ, let him be Anathema Maranatha”; while the New King James Version translates the verse including the Aramaic this way: “If anyone does not love the Lord Jesus Christ, let him be accursed. O Lord, come!” (emphasis added throughout).

- Matthew 27:46 records a cry in Aramaic by Jesus when He was on the cross: “And about the ninth hour Jesus cried out with a loud voice, saying, ‘Eli, Eli, lama sabachthani?’ that is, ‘My God, My God, why have You forsaken Me?’”

For further study

It is interesting to learn about the small portions of Aramaic that were included in the original writing of the Bible. But our study of God’s Word and how we need to live in accordance with God’s expectations is of even greater importance. To learn more about how the Bible was written and what God wants us to do, see articles in the Bible section.